WeChat, more commonly known by its Chinese name, 微信 (wēi xìn), is the app installed on nearly every Chinese person’s phone. Its ubiquitousness is, in a large part, due to its wide range of features: instant messaging, social media, mobile payments, mini-games, and more. The sheer population using the app in China creates a web of users that makes it even more indispensable.

WeChat was developed in 2011 by Tencent, a Chinese technology conglomerate. In 2018, it became the largest standalone mobile app in terms of the number of users. Now, WeChat has over 1.2 billion users, which is around 15% of the global population. While the vast majority of WeChat users (around 70%) come from China, the app has a sizable user base of 4 million people in the United States. Comparatively, there are around 5 million Chinese immigrants or Chinese-Americans living in the United States, according to the Pew Research Center.

During the first Trump administration, the government issued an order to ban WeChat and TikTok, citing national security concerns. The order was set to go into effect on September 20, 2020, but was blocked by a California judge. Later, Joe Biden paused legal action against the two apps. Currently, Trump has not shown signs of wanting to push another ban.

Many first-generation Chinese immigrants use WeChat to connect with their family and friends abroad. Along with facilitating international video calls, WeChat also sports a feature called Moments (in Chinese, the feature is called 朋友圈, which literally means “friends’ circle”). Similar to Instagram, Moments allows users to post images and text to their feed, though posts are only available to selected friends of the user on the app.

Aside from connecting with those overseas, there are also thriving, localized WeChat groups composed of first-generation Chinese-Americans. Chinese parents living in the same neighborhood or whose children go to the same school often create WeChat groups. Businesses involving food ordering, tutoring or online classes, and college counseling — often, but not always, run by Chinese people — also use WeChat to advertise to and organize their Chinese-American user base.

Clearly, for many older Chinese-Americans, WeChat is a hub of activity. But what about for their children? The AAPI Angle polled twelve second-generation Chinese-American teenagers from across the United States about their relationship with WeChat.

Of these, ten responded that their parents used WeChat frequently, while two responded that their parents used WeChat, but not often. Benjamin, a high schooler from Tennessee, stated that while he uses WeChat “once in a blue moon,” his parents practice “extreme amounts of usage.” He wrote, “My mom makes so many Moments posts every week.”

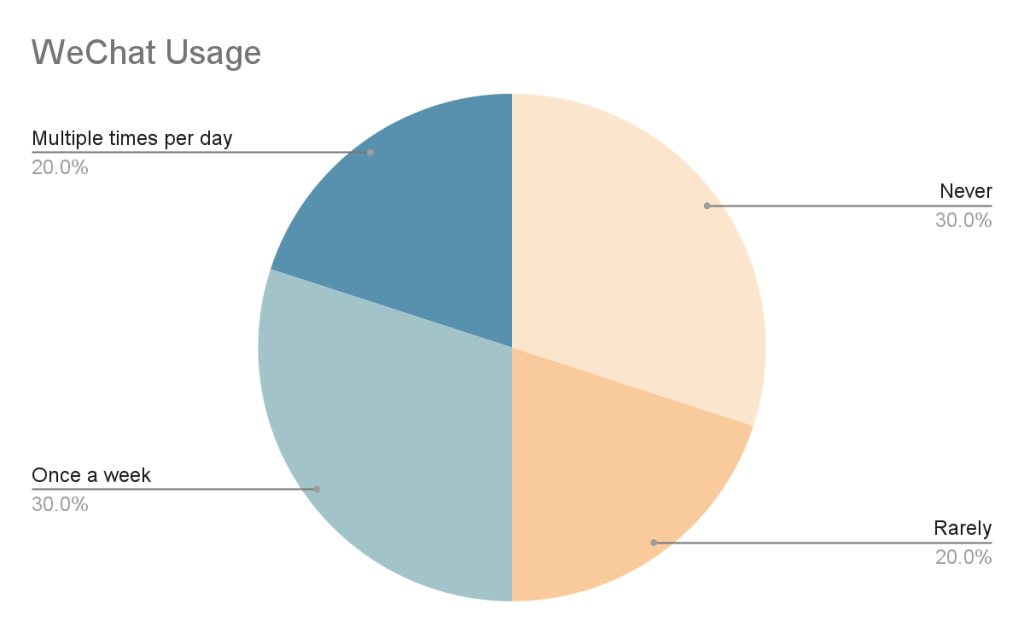

Ten of the twelve teenagers polled responded that they also did own WeChat. On the other hand, of these ten, five reported to “rarely” or “never” using the app. The remaining five reported using the app “once a week” or “multiple times per day.”

Above: WeChat usage for the ten respondees who own the app

Maria, a high school senior from Washington, indicated that she uses WeChat multiple times per day. She elaborated that she mainly used WeChat for WeChat Channels, a feature that allows users to create and share short videos, similar to TikTok. “I use WeChat Channels to doomscroll,” Maria stated. Although Maria also watches Instagram Reels, she mentions preferring WeChat Channels, as it “just has better Chinese content,” indicating a strong interest in the Chinese aspect of her Chinese-American identity.

On the other hand, Tiffany, from New Jersey, who also checks WeChat multiple times per day, responded that she uses WeChat mainly for “chatting in the family [group chat] and talking with international student friends.” Similarly, two other respondees mentioned using WeChat to talk to their grandmother and art teacher, respectively. Other uses of WeChat mentioned included playing mini-games or posting Moments.

Although it is nowhere near as common for second-generation Chinese-Americans to use WeChat as their parents, the younger crowd is clearly aware of and willing to experiment with the app. Rather than creating the centralized hub that it does for the parents, though, WeChat provides a different experience for each of its teenage Chinese-American users.

With a single click, WeChat connects grandparents with their grandchildren, teachers with their students, and friends with each other, even if there are literal oceans between them. The app ties a string between these teens and a critical part of their identity. Like all social media platforms, WeChat can be addictive and time-wasting. But, perhaps unlike Instagram or Snapchat, WeChat does so across borders.

Leave a comment